Paul Johnson is a Military & Aviation Historian, Researcher, Author and occasional Battlefield Guide.

This site is owned and operated by Paul Johnson

This is the post excerpt.

This site is owned and operated by Paul Johnson

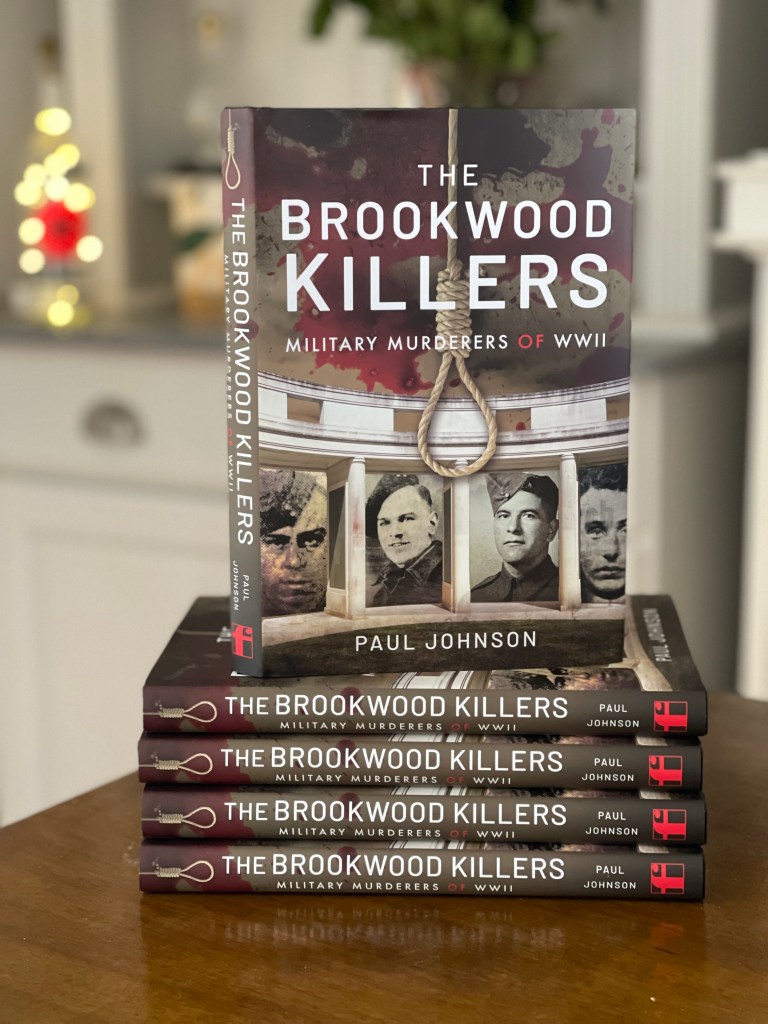

Nestled deep in the Surrey countryside stands the Brookwood 1939-1945 Memorial. Maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, its panels contain the names of nearly 3,500 men and women of the land forces of Britain and the Commonwealth who died in the Second World War and who have no known grave. Among the men and women who names are carved on the memorial are Special Operations Executive agents who died as prisoners or while working with Allied underground movements, servicemen killed in the various raids on enemy occupied territory in Europe, such as Dieppe and Saint-Nazaire, men and women who died at sea in hospital ships and troop transports, British Army parachutists, and even pilots and aircrew who lost their lives in flying accidents or in aerial combat. But the panels also hide a dark secret. Entwined within the names of heroes and heroines are those of nineteen men whose last resting place is known, and whose deaths were less than glorious. All were murderers who, following a civil or military trial, were executed for the heinous offence they had committed. The bodies of these individuals, with the exception of one, lay buried in un-consecrated ground. As Paul Johnson reveals, the cases of the Brookwood Killers’ are violent, disturbing and often brutal in their content. They are not war crimes, but crimes committed in a time of war, for which the offender has their name recorded and maintained in perpetuity. Something that is not always applied in the case of the victim.

Read the latest reviews of my recent publication, “The Brookwood Killers” here;

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/The-Brookwood-Killers-Military-Murderers-of-WWII-Hardback/p/20588

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system and is bestowed for acts of valour in the presence of the enemy to members of the British and Commonwealth Armed Forces. A total of 1,358 awards of the VC have been made since its inception on 29 January 1856, with just three servicemen being the granted the award on a second occasion.

Given its rarity, and the circumstances in which the award is achieved, it is not surprising to find numerous plaques and memorials to VC recipients across the world. Whether it is in the location where the action took place, a street or building named after the individual, or perhaps a school or church they attended, a majority recognise the achievements of an individual. Occasionally, a collective of recipients can be found listed at a Regimental museum or depot, a university or college, but it is unusual to find more than one listed on a local war memorial, particularly where it relates to one particular period such as the Second World War. Much rarer, is to find the award being made to a single family, in the same period, on the same memorial.

If you make a visit to the small Hertfordshire town of Radlett, you will find, situated on the ancient roadway named Watling Street, a memorial listing the men and women from the town who gave their lives in two world wars. Amongst the names of those added following the cessation of hostilities in 1945 are Leslie Manser VC and John Randle VC. Not only is this very unusual but, to my knowledge, unique within the United Kingdom.

Their life stories bear some striking resemblances, they are bonded by a single-family link and their demise occurred equally in circumstances of gallant self-sacrifice.

Leslie Thomas Manser VC

The story of Leslie Manser begins with his father, Thomas James Stedman Manser, a British civil servant who was born in India on the 24th October 1883. At the age of 15, Thomas began work with the Indian Post and Telegraph Department, part of the India Office, being employed as a telegraphic engineer, a career that would last for some 37 years and would see him retire as a Divisional Engineer. Thomas married Rosaline Ellen Louise Edwardes on the 25th October 1911. Their first child, Mavis Ellen, was born on the 27th July 1912, and a son, Cyril James, was born on the 15th September 1916. Their third child, Leslie Thomas Manser, was born in New Delhi, India, on the 11th May 1922.

Young Leslie became a student of the Victoria Boys’ School, Kurseong, Darjeeling, and in December 1936, when Thomas retired, the family returned to England, where they settled in Radlett, Hertfordshire. He continued his education at Aldenham School, Elstree, during which time his sister, Mavis, worked as a Stenographer for Handley-Page at Radlett airfield and his brother, Cyril, was employed in the aeronautics industry as an engineer.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Leslie volunteered as an ARP Warden in the local area but was eager to play a part in the fight against Hitler. Attempts to enlist in both the Army and Royal Navy were unsuccessful, however, in August 1940, he approached the Royal Air Force and was quickly accepted with a view to training as a Pilot. He was commissioned as a Pilot Officer in May 1941 and undertook an intensive training course that was to see him become a member of Bomber Command. Following a navigational course and final operational training with No.14 Operational Training Unit at RAF Cottesmore, he was posted to No. 50 Squadron which, at that time, was operating Handley Page Hampden’s from RAF Swinderby, in Lincolnshire.

He joined the Squadron on the on 27 August 1941 and, two days later, experienced his first operation, as a second pilot, taking part in a bombing raid on Frankfurt. During the next two months he flew six more sorties against targets including Berlin, Hamburg, and Karlsruhe before being posted to No.25 Operational Training Unit, at RAF Finningley, on 7 November 1941. A month later he was posted back to No.14 Operational Training Unit, but this time as an instructor.

After serving briefly with No. 420 Squadron, RCAF, Leslie re-joined No.50 Squadron in April 1942 which, by then, was operating from Skellingthorpe, and converting to the new Avro Manchester heavy bomber. He piloted one of the new aircraft during a leaflet drop over Paris and flew a further five sorties during April and May. Leslie was promoted to Flying Officer on 6 May 1942, just five days before his 20th birthday.

On night of the 30/31 May 1942, the RAF launched the first of its ‘thousand bombers’ raids, a devastating attack on the city of Cologne. The aircraft used were a mixture of Whitleys, Wellingtons, Hampdens, Stirlings, Halifaxes, Manchesters and Lancasters, a force of 1,046 bombers along with an assortment of night fighters in support.

On the morning of 30th, Manser and another pilot were instructed to collect two Manchesters from Coningsby, Lincolnshire. As many of these aircraft were drawn from reserves and training squadrons, it was inevitable that many would be in poor condition. Manser’s aircraft was no exception, it had no mid upper turret and a sealed escape hatch.

That evening Manser and his crew took off in L7301 ‘D’ Dog, with a full bomb load of incendiaries. The aircraft, now difficult to manoeuvre, was unable to reach an altitude of more than about 7,000 ft. Hoping the main bomber force would attract the greater concentration of flak, Manser decided to continue on. As he came over the target, his aircraft was caught in searchlights and was hit by flak. In an effort to escape the anti-aircraft fire he took violent evasive action, which reduced his altitude to only 1,000 ft (300 m) but he could not escape the flak until he was clear of the city. By this time, the rear gunner, Sgt Naylor, was wounded, a bomb bay door blown off, the front cabin full of smoke and the port engine overheating.

Rather than abandon the aircraft and be captured, Manser tried to get the aircraft and crew to safety. The port engine then burst into flames, burning the wing, and reducing airspeed to a dangerously low level. The crew prepared to abandon the aircraft which, by then, was barely controllable and a crash inevitable. The aircraft was by now over Belgium, and Manser ordered the crew to bail out. It was Sergeant Leslie Baveystock’s job to fit a chest harness to Manser, but he refused the offer of a parachute as he was acutely aware that as soon as he let go of the controls the aircraft would stall and crash. He ordered Baveystock to leave the stricken aircraft and remained at the controls, sacrificing himself to save his crew. As they parachuted down, they watched the bomber crash into a dyke at Bree, north east of Genk, where it burst into flames. Manser did not escape.

His crew, with the exception of Pilot Officer Barnes who was captured by the Germans, were helped by local Belgians to evade capture and made their way back to the UK via France, Spain and Gibraltar. The testimonies of the five evaders were instrumental in the posthumous award of the VC. They themselves were to be awarded wither DFC’s or DFM’s.

The citation in the London Gazette of 20th October 1942 gives the following details:

Flying Officer Manser was captain and first pilot of an aircraft which took part in the mass raid on Cologne on the night of 30th May 1942. Despite searchlights and intense and accurate anti-aircraft fire he held his course and bombed the target successfully from 7,000 feet. Thereafter, although he took evasive action, the aircraft was badly damaged, for a time one engine and part of one wing were on fire, and in spite of all the efforts of pilot and crew, the machine became difficult to handle and lost height. Though he could still have parachuted to safety with his crew, he refused to do so and insisted on piloting the aircraft towards its base as long as he could hold it steady, to give his crew a better chance of safety when they jumped. While the crew were descending to safety, they saw the aircraft, still carrying the gallant captain, plunge to earth and burst into flames. In pressing home his attack in the face of strong opposition, in striving against heavy odds to bring back his aircraft and crew, and finally, when in extreme peril, thinking only of the safety of his comrades, Flying Officer Manser displayed determination and valour of the highest order.

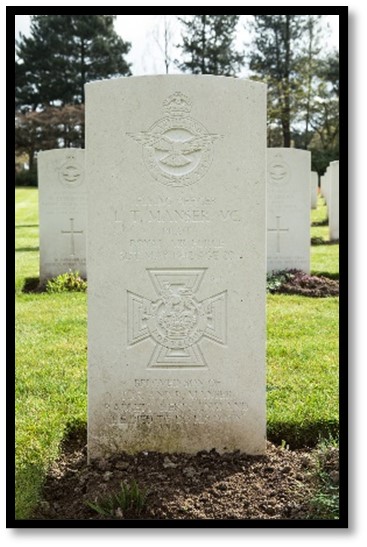

Leslie Manser was originally buried at Brusthem Airfield (St. Trond) but on the 31 January 1947 was reburied in the Heverlee War Cemetery, Belgium. His headstone is inscribed;

“Beloved Son Of T.J.S. and R. Manser, Radlett, Herts. England. – He Died To Do His Duty”

His name is recorded on the Radlett war memorial and he is also remembered on the memorial at the Victoria Boys’ School, Kurseong, Darjeeling.

The Manser School in Skellingthorpe, Lincolnshire, is named after him.

Following the devastating loss of their brother, Cyril and Mavis continued with their work in support of the war and, for Mavis, there was also now the fact that she had married a serving soldier, John Niel Randle.

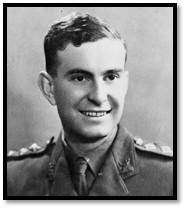

John Niel Randle VC

John Niel Randle was born in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India, on the 22 December 1917, the son of Dr. Herbert Niel and Edith Joan Randle. His father was the Librarian of the India Office Library, a Professor of Philosophy at Queen’s College, Benares and a writer on Indian philosophy.

He was educated at the Dragon School, Marlborough College, and Merton College, Oxford, where he qualified in law. One of his best friends during this time was Leonard Cheshire, who was himself awarded the Victoria Cross during the Second World War.

After being commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Norfolk Regiment in May 1940, he was quickly promoted to temporary Captain whilst serving with the 2nd Battalion, which was stationed in Hessle, Yorkshire, being billeted in Ferriby Road. John lived in the home of Dr Harley Patterson Milligan and his wife, Charlotte. It was here in 1941 that he became engaged to Mavis Ellen Manser, the sister of Leslie Thomas Manser.

The couple married in January 1942 and Mavis returned to her work at the Handley-Page factory in at Radlett. Their only son, Leslie John, was born at the end of the year. Sadly, by this time the Battalion had been posted overseas and John Randle was never to see his son.

Captain Randle was commander of ‘B’ Company, 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolk Regiment. On 4 May 1944 during the Battle of Kohima in northeast India, he was ordered to attack the Japanese flank on General Purpose Transport (GPT) Ridge during the relief and clearance of Kohima. The citation from the London Gazette reads:

On the 4th May 1944, at Kohima in Assam, a Battalion of the Royal Norfolk Regiment attacked the Japanese positions on a nearby ridge. Captain Randle took over command of the Company which was leading the attack when the Company Commander was severely wounded. His handling of a difficult situation in the face of heavy fire was masterly and although wounded himself in the knee by grenade splinters he continued to inspire his men by his initiative, courage and outstanding leadership until the Company had captured its objective and consolidated its position. He then went forward and brought in all the wounded men who were lying outside the perimeter. Despite his painful wound Captain Randle refused to be evacuated and insisted on carrying out a personal reconnaissance with great daring in bright moonlight prior to a further attack by his Company on the position to which the enemy had withdrawn.

At dawn on 6th May the attack opened, led by Captain Randle, and one of the platoons succeeded in reaching the crest of the hill held by the Japanese. Another platoon, however, an into heavy medium machine gun fire from a bunker on the reverse slope of the feature. Captain Randle immediately appreciated that this bunker covered not only the rear of his new position but also the line of communication of the battalion and therefore the destruction of the enemy post was imperative if the operation were to succeed.

With utter disregard of the obvious danger to himself Captain Randle charged the Japanese machine gun post single-handed with rifle and bayonet.

Although bleeding in the face and mortally wounded by numerous bursts of machine gun fire he reached the bunker and silenced the gun with a grenade thrown through the bunker slit. He then flung his body across the slit so that the aperture should be completely sealed. The bravery shown by this officer could not have been surpassed and by his self-sacrifice he saved the lives of many of his men and enabled not only his own Company but the whole Battalion to gain its objective and win a decisive victory over the enemy.

Originally buried in the location named Norfolk Ridge, the body of John Randle and the men of the Royal Norfolk Regiment were reinterred in what is now Kohima Military Cemetery on the 15 August 1944.

His headstone is inscribed, “Remembered By His Devoted Wife, Only Son Leslie John, Parents And Sisters”. His name, like that of Leslie Thomas Manser VC, is recorded on the Radlett war memorial in Hertfordshire.

Despite the devastating blow of losing her brother, and then her husband, Mavis found love again and on the 6 September 1952 married Richard Andrew Charles Lowndes. She passed away on the 23 January 2008 at the age of 95. Remember Them.

Sources:

During a visit to the National Archives I came across a story that, whilst initially horrific, demonstrated how strange life can be and how, despite all that comes our way, love can sometimes still shine through.

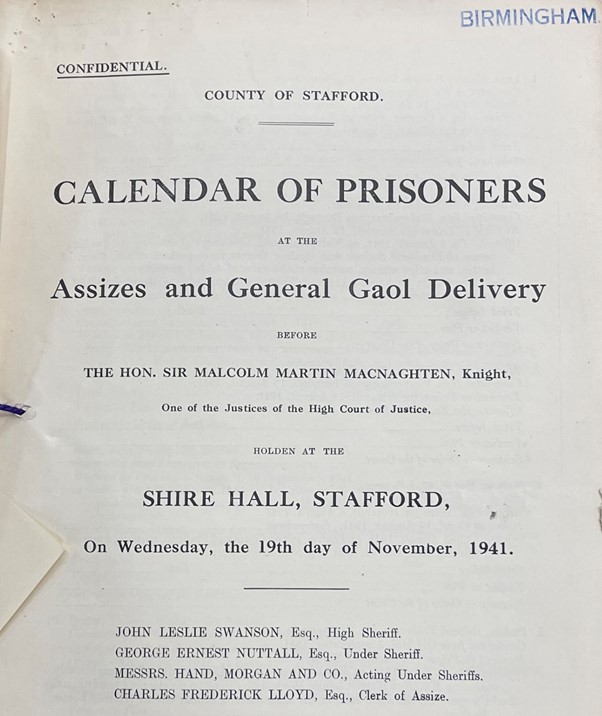

On Wednesday 19 November 1941, The Honourable Sir Malcolm Martin Macnaghten, a Justice of the High Court, presided over 16 criminal cases held at the Shire Hall, Stafford. Of these, 6 involved serving British soldiers. Two were charged with Bigamy, one with Rape, one for Murder and two for Attempted Murder.

A case of attempted murder was heard against 23 year-old Private Samson Cross, of 14, Burn Street, Chadsmoor, serving with the South Lancashire Regiment. He had been named after his uncle, Samson Cross, who was reported missing on the 13 October 1915 at Loos, whilst serving with the 1st/6th South Staffordshire Regiment.

On the morning of 15 September 1941, Cross told a Policeman, P.C. Weaver, he had murdered his girlfriend, 19 year-old Vera Muriel Woollaston, who lived at 8, Burn Street, Chadsmoor. They had known each other for many years but had been “keeping company” for six months at which point there had been a “tiff” between them. On that morning, Vera was doing housework when Cross called at her home and asked if they could come to some understanding. She replied: “You should know by now.” He asked her for a letter he had written to her and when she handed it over, he tore it up. She was then bending down to change her boots when Cross put his hands around her throat and attempted to strangle her, after which he picked up a hammer and struck her on the head. She fell to the floor, and Cross left the house.

He approached P.C. Weaver saying, “I have just murdered a girl by hitting her with a hammer and strangling her.” The Policeman entered the house where he found a pool of blood on the kitchen floor and a blood-stained hammer on the table. Cross made a statement describing how he attacked Vera, adding, “I intended to kill her, but my nerve failed me.” He appeared at Cannock Police Court on 23 September 1941, and was held in remand until his case could be heard at the assizes.

Vera, however, had survived the attack, all she remembered was finding herself lying face downwards and alone in the room. She had no recollection of being struck. Her injuries were, it seems, quite minor. Cross pleaded guilty to wounding Vera but not guilty to a more serious charge of wounding with intent to murder. He was described by his defence as a man of good character, who had acted in an isolated outburst of violence committed while in a fit of jealousy. Macnaghten sentenced the soldier to be bound over on good behaviour for three years. He also made a condition that Cross could not go within 10 miles of Vera’s home without the written permission of her father or grandfather with whom she lived.

It seems that permission was soon granted, as Samson and Vera were married just a few weeks later. They had one child, Samuel, who was born in December 1945 (passed away 2011). Despite this dreadful incident, they remained together for more than 40 years, until 7 November 1984 when Vera passed away aged 62. Samson, seemingly broken-hearted, died just three weeks later.

Remember Them.

Source:

National Archives – HO144/21640

Ancestry (Vera Muriel Cross)

(Source: Martin Sugarman – Jewish Historical Society of England)

One of the CWGC burials in the East Ham Jewish Cemetery is that of 20 year-old Private Mark Feld, a cook serving with the Army Catering Corps and attached to No.258 Company, Pioneer Corps, stationed at Marlborough Farm Camp, Burton Dassett, in Warwickshire.

His story, although sadly not unique, is one that reveals the brutality of service life at a point in British military history where the United Kingdom had started to settle into post-war drudgery. The men of its armed forces, who had served across the world during the Second World War, had begun to return to their homes, and their places were now being filled with recently conscripted young men under the national service scheme.

In the Summer of 1946, there was considerable disgruntlement amongst some of these men and, as a result, discipline began to suffer. Urgent action needed to be taken to bring the situation under control. So tough enforcers were called for, one of these being Sergeant Patrick Francis Lyons, a 35 year-old experienced soldier, and strict disciplinarian. He was made the Provost Sergeant at the camp, and it was felt that his presence soon brought about a change in discipline amongst the soldiers stationed there. One of those men for whom Lyons appeared to have a particular dislike was Private Mark Feld, a young Jewish soldier, the son of Harry and Bessie Feld, of Stamford Hill, London.

On the night of the 18 August 1946, Private Feld was asleep in the Cooks hut at Marlborough Farm Camp. At 1am, Private Ivor Davies, laying awake in the same hut, heard the sound of someone trying the door handle at the rear of the hut. This attempt was unsuccessful, so the individual came to the front of the hut and tried the handle, this time it opened. Suddenly, an electric torch lit up the hut, and Davies saw Sergeant Lyons walk up to Private Feld and strike him a single blow with a military police truncheon.

Five minutes after this attack, Private Feld was seen to get up, get dressed and walk out of the hut. Lance Corporal James Kelly, who was on guard duty, saw Feld walking towards him with blood on his face. He spoke to him and Feld stated that he didn’t know what had happened. He reached the Camp Reception Station where Sergeant G. W. Gilchrist, R.A.M.C., put a stitch into a cut above his left ear, then dressed the wound. He described Private Feld as being “in fighting condition and struggled desperately as I inserted the stitch”.

The following morning Mark Feld was found unconscious in his bed. He was seen by Dr. D. S. Williams, of Fenny Compton, who concluded he was suffering from compression of the brain and ordered his removal to Warwick Hospital. When he arrived at the hospital it was decided to move him to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham. On the way there, as they approached Solihull, Private Feld died in the rear of the ambulance. Dr. J. C. Colbeck, Warwickshire County pathologist, stated at an inquest that the young soldier had a laceration passing right through the scalp, three inches above his left ear. The injury was most likely caused by a truncheon. Death was due to compression of the brain caused by hemorrhage as a result of a fracture of the skull.

Following his death, the Police were called to the camp and Sergeant Henry Storey Crampsie, who had accompanied Lyons when he made the attack, gave a statement in which he said he had spoken to Lyons earlier that evening about Feld, with whom he had had trouble previously. Lyons said, “I will get Feld before many nights.” He accompanied Lyons to Feld’s hut, but denied taking part in the affair, even though he knew what was going to happen.

Sergeant Crampsie later told Magistrates that he left the kitchen of the Sergeant’s dining room with Lyons at about 12.20 a.m. and they went towards the guard-room. On the way Lyons said, “I will show you how I’m going to do up Feld.” Lyons then went into the guard-room and brought out a military police truncheon and an American-type torch. The pair went to the cooks’ hut where Private Feld was sleeping and tried the back door, but it was locked so they went to the front door of the hut. Sergeant Lyon went in and Crampsie followed him. After flashing his torch round the hut he walked to the other end where Private Feld was sleeping. Crampsie saw him go to Feld’s bed, raise his right hand in which he held the truncheon, and bring it down with a thud. He claimed he only heard one blow. The two NCO’s then left the hut and Lyons said, “That’s got that job over. You stand by me and I will stand by you “, to which Crampsie agreed. The next morning, Lyons said to Crampsie, “You look worried. I know by your face you are going to give the game away”.

The Police later confronted Lyons with the statement made by Sergeant Crampsie. After reading it Lyons threw the statement down on the table and shouted “Lies, all lies.” Asked what he did do at the time in question, Lyons said he went for a run round the garrison after leaving the kitchen of the sergeants’ dining room, and then moved a lorry from outside the N.A.A.F.I. Lyons was then arrested and taken to Stratford-on-Avon, where he made a statement after which he was charged with murder.

Lyons was committed for trial at Warwick Assizes on 28 November 1946. A staff biologist from the West Midland Forensic Laboratory gave evidence that he examined the truncheon handed to the police by Lyons, and on its end he found a single small blonde hair which corresponded exactly with Feld’s hair. This was the piece of evidence that sealed his fate. Lyons protested that it was not his intention to kill Mark Feld but simply to “bring him into line”. Following a long deliberation, Sergeant Patrick Francis Lyons was found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter and was imprisoned for 10 years penal servitude.

Mark Feld’s headstone is inscribed; Mourned By Your Loving Mother, Father & Family. May Your Dear Soul Rest In Peace. A year after his death, his brother, Simeon Feld, was to see a son born, who was named Mark in honour of his fallen uncle. This young man, somewhat rebellious and seeking his own way in life, was not to become a soldier but, instead, would grow to be one of the UK’s most talented artists of the glam rock scene. You may know him better as the lead singer of T-Rex, Marc Bolan.

Remember Them.

Sources:

National Archives – ASSI 13/124

National Archives – ASSI 88/20

Banbury Guardian – Thursday 26 September 1946

The 10th of July 1940 is recognised as the first day of the Battle of Britain, and it was on this opening day of one of the most monumental events in British history that Pilot Officer Gordon Thomas Manners Mitchell, of No.609 (Auxiliary) Squadron, Royal Air Force, was to see his aircraft become an initial casualty of the conflict. His charge that day was a Supermarine Spitfire (N3203) which had been involved in an engagement with German fighters during an afternoon patrol and had to make a forced landing at Middle Wallop airfield in Hampshire. Mitchell, who had encountered the enemy previously, had survived the day, but this was to be the last time, and he was soon to become one of the first of the few.

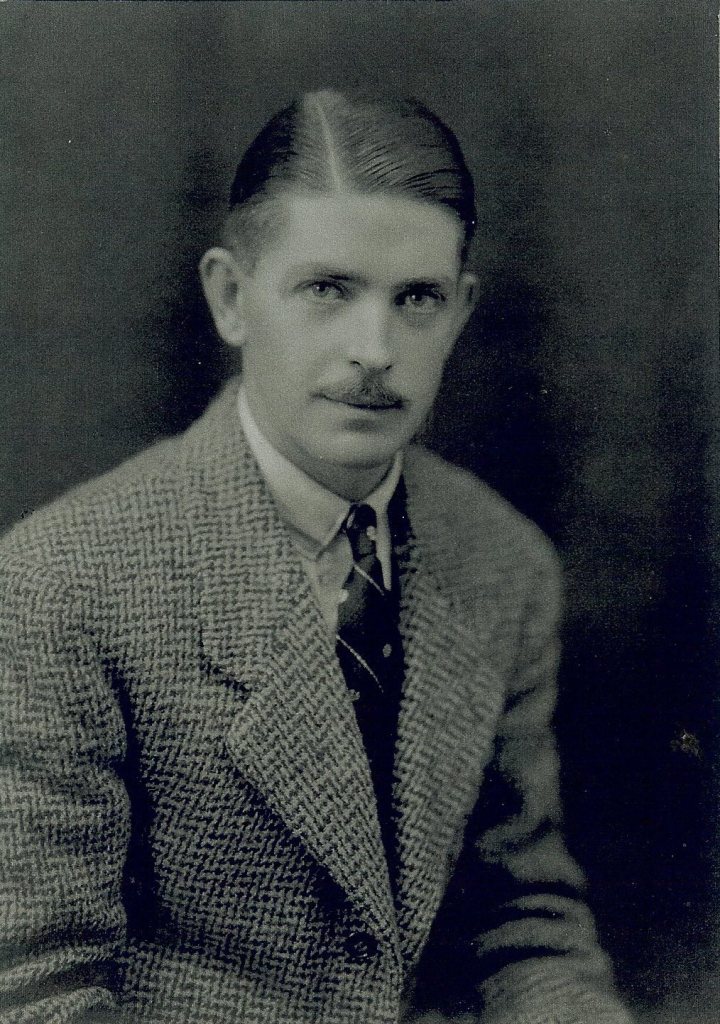

Born in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon) on the 29th September 1910, the only son of Thomas Robert & Agnes Mitchell (nee Manners). His father was a Chemist by profession and was later to become a Director of Commercial Company General Stores. The family moved to a large home named “Graylands”, in The Broadway, Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire, and Gordon was first educated at Caldicott School in Hitchin. He later attended the Leys Public School in Cambridge, and it was here that he was to meet David Crook and Geoffrey Gaunt who were also both destined to be become part of “The Few” and who served with Gordon in No.609 Squadron.

Mitchell and Crook, in particular, were to become great friends and Crook describes him in his book “Spitfire Pilot” as a “Delightful person, a very amusing and charming companion, and one of the most generous people I ever knew, both as regards material matters and, more important still, in his outlook and views. He was a brilliant athlete, a Cambridge Hockey Blue and a Scottish International. It always used to delight me to watch Gordon playing any game whether Hockey, Tennis or Squash because he played with such natural ease and grace, the unmistakable sign of a first class athlete.”

In October 1929, Gordon became a student at Queens College Cambridge reading Economics and Law and also quickly became involved in the University Hockey team. This would lead to him becoming involved with the Scottish International team with whom he received his First cap against Ireland in 1930. In those days, unlike to-day, your links with another country had only to be tenuous in order for you to become a player in their International sporting teams, and this was the case with Mitchell.

The following year was to prove a busy one for Mitchell as he was to become firstly a Cambridge Hockey Blue and also Secretary of the Hockey Club. In addition he also managed to find time to complete his studies and gained a Third class Pass in Economics. In 1932 Gordon Mitchell became the Captain of the Cambridge Hockey Team and was also capped for Scotland against his native England. Again, as in 1931, he found time to complete his studies and gained a Third Class pass in Law, and then left Cambridge University in June 1932. Now described as a man of “independent means” it seems he spent the interim years working and travelling in the Far East but, with the clouds of war looming, opted to return home to England, where he wanted to learn to fly.

Gordon joined the Auxiliary Air Force on the 11th November 1938. A volunteer force that was primarily made up of young men with prominent and wealthy backgrounds, he was soon commissioned as a Pilot Officer into No.609 Squadron based at Yeadon (Leeds). On the 24th August 1939 he was called, along with many other Auxiliary Pilots, to full-time service, arriving at Yeadon on the 25th. However, on the 27th, No.609 moved to its first wartime station at Catterick, forty miles to the North, but Mitchell was left behind with several other pilots including Crook and Gaunt and another pilot ,who was to become a great friend of Mitchell’s, Michael Appleby.

They spent the next month at Yeadon during which they utilised their time playing games against the WAAF.’s who Crook says were chosen, “for their decorative, rather than athletic qualifications” but they did not perform any flying. Then, on the 7th October 1939, they were posted to No.6 Flying Training School at Little Rissington in Gloucestershire, and at last Mitchell was to get the chance to do some flying. The Flying Training School initially proved to be a rather unfriendly place where Mitchell and the others found themselves having to conform to regular RAF disciplines, including Parade at 07.45am. They also found it difficult, at first, for men in their late twenties to adjust to a system designed for eighteen and nineteen year-olds, but they worked hard and were soon to become one of the best courses the school had ever seen.

On the 4th May 1940 Mitchell re-joined No.609 Squadron at Drem in Scotland, along with Crook, Appleby and Gaunt. They spent the following two weeks “working up” on Spitfires. Then on the 19th May the squadron was posted to No.11 Group at Northolt in preparation for the Home Defence.

(L-R) David Crook, Michael Appleby, Phillip Barran and Gordon Mitchell

Mitchell’s first operational flight, on the 1st June 1940, proved to be a tragic one. He was flying as No.3 in a Section of Spitfires with two regular pilots who had joined No.609 from other Squadrons, Flying Officer Edge and Flying Officer Ian Bedford Nesbitt “Hack” Russell, an American. Whilst performing a patrol over the Dunkirk evacuation area Mitchell, whilst in a turn, became separated from the others. As Edge and Russell searched for their lost comrade they were attacked by a Bf110 and Russell was hit. Edge describes what happened as he searched for Mitchell , “I saw Hack, surrounded by bursting shells and tracer, pull up in a near vertical climb, then fall off in a stall and commence a long slow spiral into the sea. I followed him down till it was obvious he was not in control.” Edge was later credited with the destruction of Russell’s attacker.

On the morning of 13th June 1940, Winston Churchill flew to France in a vain attempt to persuade the French Government to carry on fighting. The De Havilland D.H.95 Flamingo in which he was being flown was escorted by nine Spitfires of No.609 Squadron, one of which was piloted by Gordon Mitchell. The Prime Ministers aircraft was far too slow for the sleek fighters and they had to keep breaking off in order to prevent their engines from overheating. Eventually, they landed at a rather unkempt grass landing strip and the pilots waited whilst the Prime Minister negotiated with the rather disinterested French statesmen. The pilots soon found themselves facing an overnight stay and, deprived of a night out in Paris, frequented a local Bistro which resulted in a substantial amount of local vino being consumed. Life seem filled with both excitement, fun and tragedy.

Final Flight

On the morning of 11th July 1940 “B” Flight took off from RAF Warmwell, a satellite airfield to Middle Wallop, following a report that a convoy was under attack from several enemy aircraft. The flight of five Spitfire’s consisted of Green Section, Bernard Little & Johnny Churchin, and Blue Section, Flight Lieutenant “Pip” Barran, Jarvis Blayney and Gordon Mitchell, who was flying Spitfire L1095. They reached a point, some 15 miles off of Portland Bill, where they found about nine JU87 “Stuka” dive bombers attacking several ships. Barran ordered Green section to cover the skies above whilst he led Blue section into the attack. Almost immediately, a Staffel (Squadron) of Messerschmit BF109 Fighters of 111/JG27 “bounced” the Spitfire’s from out of the sun. The first Green section knew of it was when Blayney saw tracer bullets surrounding his Spitfire and had to make a severe manoeuvre in order to avoid being hit, although he did manage to get a deflection shot in and destroyed one of the Stuka’s. Blayney had tried to warn the others but they may, in their excitement, have left their radios in the transmit mode and therefore would not have heard his desperate warning cry.

Within a few minutes Blayney found himself alone and began circling a burning ship, then he saw Barran’s Spitfire heading towards the coast, it was trailing vapour, the prop was slowly spinning to a halt and the canopy was open. Barran baled out and Blayney circled his position and radioed for help, not realising that Barran was badly burned and wounded. A rescue launch eventually reached him but shortly after being taken aboard he died from a combination of his burns, wounds and exposure.

The last anyone had seen of Gordon Mitchell was as he was diving into the attack, but he had been quickly shot down by Oberleutnant Max Dobislav. An extensive Air/Sea search failed to recover Mitchell’s body and he was presumed lost. Some days later his body was washed up on a beach at Brook on the Isle of Wight.

The location at Brook, Isle of Wight, where the body of Gordon Mitchell was washed ashore.

On Thursday 25th July 1940 David Crook travelled to Letchworth in the station ambulance with the body of his dear friend for the funeral. To-day Mitchells grave lies in the little church of St.Mary’s in Willian. The last resting place of one of the First of the Few.

His name is recorded on one of the plaques at Letchworth Railway Station listing the names of those who did not return to the Garden City. He was 29 years-old.

Postscript

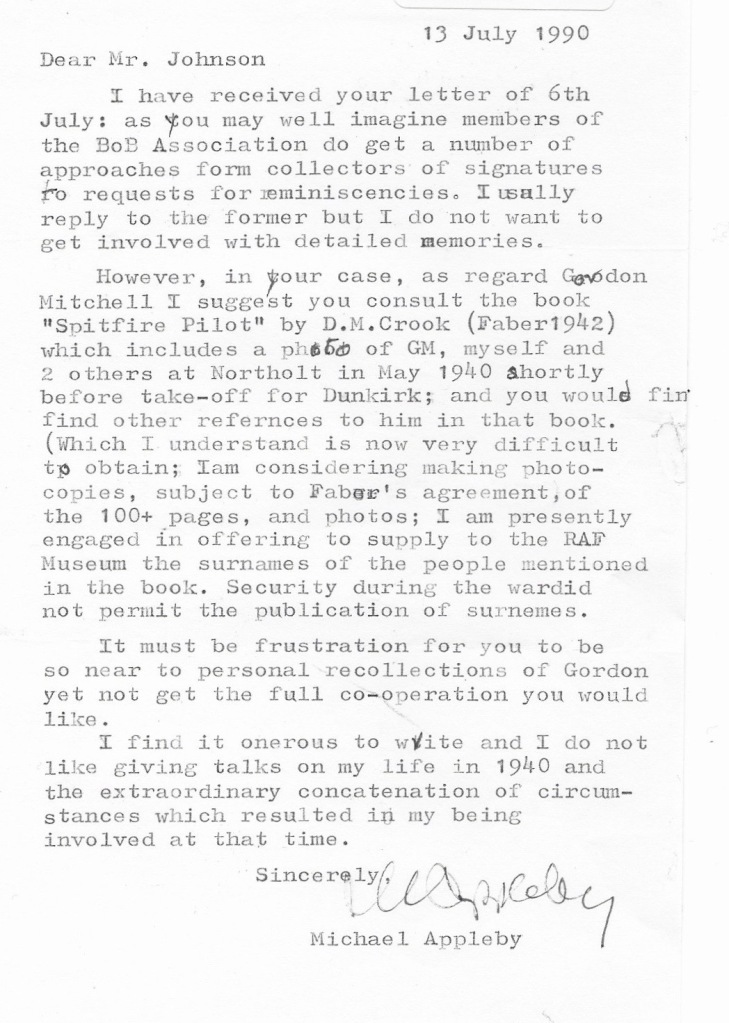

Thirty years ago, as a fledgling and somewhat naive researcher, one of the most interesting aspects of my investigation into this story, is the fact I suddenly discovered not all veterans like to talk about their wartime experiences. Through the Battle of Britain Association I was able to contact Michael Appleby, one of Gordon Mitchells close friends. He wrote to me in July 1990, stating that he found writing “onerous”, and did not like talking about his life in 1940.

Given the high esteem in which these men were held, I was more than a little surprised that Michael did not really want to discuss his friends demise, but was happy in the knowledge that he had given me a little pointer, and I still have the copy of David Crook’s “Spitfire Pilot” in my library that Michael recommended.

Over the passing years, having met many veterans, studied thousands of books and documents, and read some very detailed personal accounts, my understanding of how these courageous young men helped to ensure our nation remained free during one of its darkest moments in history has expanded immensely, and I now not only appreciate their sacrifice but realise, given the intensity of life through the war years, why they could not bring themselves to talk about their lost comrades. Remember Them.

First of the Few to Fall – Pilot Officer Gordon Thomas Manners Mitchell. No.609 Squadron (AAF). Killed in Action on 11 July 1940 aged 29. Read his story here;

Tweet

Very proud to announce the publication of my latest book, co-authored with Dan Hill, which will be released in April 2020 via Pen & Sword publications. Why not pre-order your copy here : https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Hertfordshire-Soldiers-of-The-Great-War/p/17710

Ploegsteert Wood, known to British troops as Plugstreet, lies approximately eight miles south of the city of Ypres (Ieper) and, technically speaking, just south of the Ypres Salient. There were no major battles fought here, and the wood itself remained mainly in British hands for much of the war. However, men from both sides fought and died in the trenches and dressing stations within and surrounding the wood on a daily basis, and an eerie sensation of stillness and silence can sometimes be felt by those visiting the wood.

Visitors to Ploegsteert will find a combination of cemeteries and memorials in the area which commemorate those who lost their lives in this sector of the Western Front. The Ploegsteert Memorial, unveiled by the Duke of Brabant on the 7th June 1931, commemorates more than 11,000 servicemen of the United Kingdom and South African forces who died in this sector during the First World War and have no known grave. The memorial covers the area from the line Caestre-Dranoutre-Warneton to the north, to Haverskerque-Estaires-Fournes to the south, including the towns of Hazebrouck, Merville, Bailleul and Armentieres, the Forest of Nieppe, and Ploegsteert Wood. The original intention had been to erect the memorial in Lille. It does not include the names of officers and men of Canadian or Indian regiments, as they are recorded on the memorials at Ypres, Vimy and Neuve-Chapelle. Those lost at the Battle of Aubers Ridge, on the 9th May 1915, who were involved in the Southern Pincer are commemorated on the Le Touret Memorial.

The Berks Cemetery Extension, in which the memorial stands, was begun in June 1916 and used continuously until September 1917. At the Armistice, the extension comprised Plot I only, but Plots II and III were added in 1930 when graves were brought in from Rosenberg Chateau Military Cemetery and Extension, about 1 Km to the north-west, when it was established that these sites could not be acquired in perpetuity. Rosenberg Chateau Military Cemetery was used by fighting units from November 1914 to August 1916. The extension was begun in May 1916 and used until March 1918. Together, the Rosenberg Chateau cemetery and extension were sometimes referred to as ‘Red Lodge’.

Hyde Park Corner (Royal Berks) Cemetery is separated from Berks Cemetery Extension by the N365. It was begun in April 1915 by the 1st/4th Royal Berkshire Regiment and was used at intervals until November 1917. Hyde Park Corner was a road junction to the north of Ploegsteert Wood. Hill 63 was to the north-west and nearby were the ‘Catacombs’, deep shelters capable of holding two battalions, which were used from November 1916 onwards.

Strand Military Cemetery lays a few hundred yards along the N365 leading from the Ploegsteert Memorial and stands at a point known by British Troops as ‘Charing Cross’. This was a point at the end of a trench called the Strand, which led into Ploegsteert Wood. The cemetery was not used between October 1914 and April 1917, but in April-July 1917 Plots I to VI were completed. Plots VII to X were made after the Armistice, when graves were brought in from some small cemeteries and from the battlefields lying mainly between Wytschaete and Armentieres.